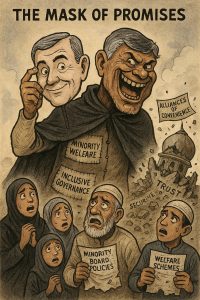

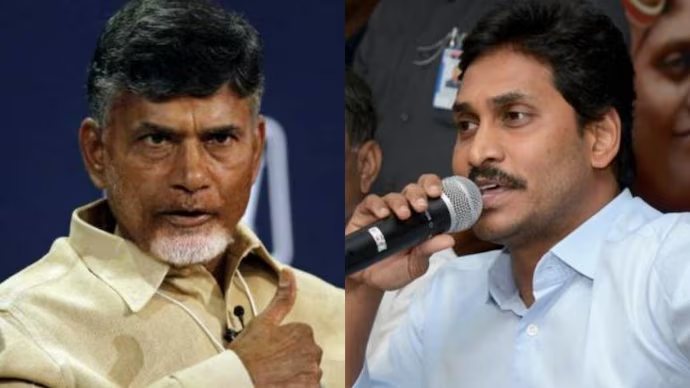

As the Telugu Desam Party (TDP) government rolls out new initiatives, a striking narrative has emerge that invites comparisons with the preceding YSR Congress Party (YSRCP) regime. Critics and observers alike are questioning whether these programs represent genuine governance innovations or mere replications of schemes introduced during Y.S. Jagan Mohan Reddy’s tenure.

Flagship initiatives such as Manchi Prabhutvam and Parent-Teacher Meetings (PTMs) have particularly come under scrutiny. While the TDP positions these efforts as steps forward, detractors argue they are echoes of YSRCP transformative programs like Nadu-Nedu, which modernized school infrastructure and introduced English-medium education in government schools. These initiatives, implemented during the YSRCP era, not only improved educational standards but also directly addressed the concerns of parents and students, earning widespread public appreciation.

Palle Panduga vs. Nadu-Nedu

Deputy Chief Minister Pawan Kalyan’s Palle Panduga program, which focuses on minor construction projects and road repairs in rural areas, has drawn criticism for its limited scope. While aimed at improving basic infrastructure, the initiative pales in comparison to YSRCP’s Nadu-Nedu scheme, which overhauled government schools, provided essential facilities, and created a roadmap for systemic educational reform.

PTMs: A Recycled Concept?

The recently launched Parent-Teacher Meetings (PTMs) are another focal point of this debate. Introduced as a platform to bridge communication between parents and school authorities, the concept was already exsisting program . During ysrcp tenure, PTMs were an essential tool for gathering parental feedback and shaping policies like Ammavadi, which provided ₹15,000 annual incentives to support students’ education.

In contrast, TDP’s PTMs have drawn criticism for falling short of offering tangible benefits. Allegations that parents were asked to contribute funds for organizing these meetings have only added to public skepticism. YS Jagan Mohan Reddy has openly criticized the TDP, calling the initiative a mere rebranding exercise that fails to deliver meaningful outcomes for students and their families.

Missed Promises and Cosmetic Changes

Adding to the discontent is the TDP’s perceived inability to fulfill key election promises. Initiatives like Ammaku Vandanam, which were touted as flagship programs in the party’s manifesto, remain conspicuously absent. Critics argue that TDP’s governance lacks the ambition to introduce structural reforms, instead relying on cosmetic changes that replicate existing schemes.

Public sentiment appears divided. While TDP supporters hail these initiatives as evidence of the government’s focus on education and rural development, detractors view them as political strategies aimed at capitalizing on the groundwork laid by the YSRCP.

The larger question remains: can the TDP carve out its unique identity in governance, or will it continue to be overshadowed by comparisons with its predecessor? For a party aiming to reclaim political ground, the challenge lies not just in governance delivery but in offering a compelling vision that goes beyond continuity and embraces innovation.